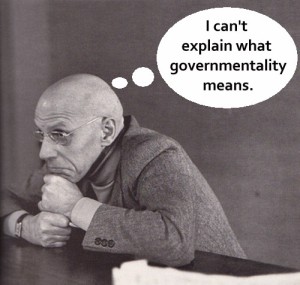

Foucault’s definition of governmentality is widely quoted but rarely criticised. Yet as I argue in Part 1 of this two-part post, Foucault’s definition is unclear and inconsistent.

This is not a major problem, because his later account is fairly clear and coherent. What is a problem, I suggest in Part 2, is that many scholars are not explicit about Foucault’s initial unclarity or inconsistency, presenting the definition as self-explanatory, and often confusing its components. My aim is not so much to chide Foucault as to warn uncautious readers that many interpreters of Foucault may not have read him closely enough. The same is doubtless true of me, of course, and I welcome efforts to correct my interpretation.

In lecture 4 of Security, Territory and Population, Foucault gives a definition of governmentality with three components.

By [governmentality] I mean three things:

1. The ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security.

This is not very clear. My guess is that if this is the first and only thing you read about governmentality, you’ll struggle to grasp what it involves. The last two-thirds of this sentence is about the kind of power which governmentality allows, and only the first third says what governmentality is – the ‘ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics’ that allow a particular kind of power to be exercised. But I’m not sure what that means.

I don’t want to sound too critical of Foucault: definitions can be hard to understand. The problem, as we’ll see in Part 2, is that Foucault’s interpreters often present this component of the definition as if it is self-explanatory: very few follow it up with the clarifications, examples or distinctions that we need to understand it.

I believe that this component of Foucault’s definition is far easier to grasp if we already have Foucault’s later usage of governmentality in our minds, especially from lectures 4, 5, 8 and most importantly 13. In these places, he seems to use the term in a relatively coherent manner: the techniques used by people in government to try to influence their citizens, and the underlying mentality of people in government. For example, a governmentality of politiques involves a police-state in the old sense of ‘police’, with domination being (literally) the order of the day, and the sovereign’s will being the key mechanism. But in the 18th century there arose a governmentality of économistes, emphasising economic ideas and tools, especially incentives; the idea of ‘police’ became relegated to what we now call ‘police officers’, whose much more minor task is to prevent certain disorders.

A governmentality is thus an approach to government, very broadly.

My interpretation is similar but not identical to the interpretations of more expert readers. Gary Gutting, for example, only mentions techniques, not mentalities; Mitchell Dean concentrates on mentalities, not techniques; Colin Gordon seems to include both. I’m confident that Foucault is referring to techniques of government, and since techniques of government rest on a mentality of government, I’ve gone for the broader view that governmentality refers to techniques and the underlying mentalities. But I’m happy to have my interpretation challenged. I’m not claiming that it’s right – though I am confident that it’s far clearer than most of the accounts mentioned in Part 2!

With Foucault’s usage of ‘governmentality’ in mind, component 1 of the definition makes much more sense.

Foucault continues with the second aspect of what he means by ‘governmentality’:

2. The tendency which, over a long period and throughout the West, has steadily led towards the pre-eminence over all other forms (sovereignty, discipline, etc.) of this type of power which may be termed government, resulting, on the one hand, in the formation of a whole series of specific governmental apparatuses, and, on the other, in the development of a whole complex of savoirs.

This is not a definition of ‘governmentality’: it’s about the growth of government, i.e. ‘governmentalization’ – a term Foucault uses in the next two paragraphs. Importantly, note that for Foucault, ‘government’ is not what we often think of in English, i.e. a set of institutions, which Foucault actually refers to here as ‘governmental apparatuses’. Rather, for Foucault ‘government’ is the type/form of power which has been defined in component 1 of the definition. (So, when I define governmentality as the techniques and mentalities of ‘people in government’, strictly speaking I mean ‘people in governmental apparatuses’).

And finally:

3. The process, or rather the result of the process, through which the state of justice of the Middle Ages, transformed into the administrative state during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, gradually becomes ‘governmentalized’.

The start is awkward: there is a big difference between a process and the result of the process. Yet neither allows Foucault to define ‘governmentality’. If he means a ‘process’, then he is simply repeating component 2 of the definition, i.e. ‘governmentalization’. If he really means ‘the result of the process’, then he is referring to the result of governmentalization, which either means the development of the type of power he calls ‘government’ (component 1), or the development of ‘apparatuses of government’ (component 2). Since he talks here about how the administrative state becomes governmentalized, he presumably means the former. But this tells us nothing about what governmentality is.

So, component 1 is hard to understand unless you already know what Foucault means by the term, and components 2 and 3 are not part of the definition, strictly speaking. Martin Saar makes a similar criticism, in the book edited by Ulrich Bröckling et al., Governmentality:

it is hard to see how something can meaningfully be said to be an ‘ensemble’ of something, a temporal ‘tendency’ and the ‘result of a process’ at the same time, the last of these only explained with the help of the term to be defined.

Perhaps something of Foucault’s meaning has been lost in translation? Yet both translations are similar (the Braidotti translation in The Foucault Effect, quoted above, and Burchell’s translation in Security, Territory and Population itself).

Of course, Foucault’s lectures were not intended as the finished product. But again, my point is less a criticism of Foucault and more a criticism of those people who repeat these definitions as if they are very meaningful – as I will argue in Part 2.

UPDATE (June 19): Clare O’Farrell, who runs the Foucault News blog, has offered her own definition of governmentality, from her book: ‘the rationalisation and systemisation of a particular way of exercising political sovereignty through the government of people’s conduct’. I like this definition a lot and am strongly tempted to drop my definition and use Clare’s in future.

Grace jieunlee

/ May 11, 2015I am reading the series of Foucault’s college de France Lecture regarding Governmentality.

Honestly, I am not satisfied with all the scholastic effort which do not represent any kind of serious reflection on this concept. I agree with Foucault’s trial in that he thought the capitalism and a sort of state power to regulate it is interrelated and its effect is the centre of modern phenomena as we recognize it throughout the recent history of world.

But I hardly understand why he explain this apparatus and effect through the centre of state power rather than the people’s desire. I tried to find out any kind of theoretical development which explain and interpret the relationship between market, state, institution and regulation throughout the people’s desire rather than intend of sovereign power. But I failed to find out such a critic.

Andrew Ihegbu

/ January 25, 2016Because there is no “people’s desire” in anything that Foucault says and that still applies today. Take the media lens off your glasses and that is clear to see. Voting does not directly affect what happens when a person is elected in any country in the world today. Every single decade, every country in the world has dozens if not hundreds of strikes and rallies, and only an handful worldwide will equate to anything. Therefore, people desire a person to lead, and the leader decides what happens after that. That ‘after that’ section is what the entire of Foucault’s writings.

This is why so many modern politicians have zero problems with ignoring promises they made whilst trying to get elected.

In the modern world, big businesses and rich individuals pay for politician’s campaigns with the promise that certain laws will be enacted. That money pays for advertising and appearances from the politician and the more of those you have the easier it is to win. Politics therefore is essentially for sale to the highest bidder: The man willing to enact the nastiest most ‘rich-serving’ laws out there will be funded the most and thus you have a state that is inherently hostile to it’s population of voters.

Regulation comes about from a ‘voters perspective’ point of view. Regulation comforts the population, and comforting the population enough to prevent economic destabilisation whilst either extracting as much funds as possible for your investors or your friends and family is really the name most government games today. Managing the population a-la Foucault is researched and calculated by the UN (do some googling and you will see that they carry out many of the mandates and recommendations regarding this), and then managed individually by countries outside the UN.

Grace jieunlee

/ May 11, 2015It is to easy and neglect explanation to attribute all the social failure to the State failure and governor’s will. All kind of problematic social phenomena would not be solved by merely abolition of capitalism or state. Even Anarchy is not the alternative of capitalist state. Before all of these attempts we need to look through the individual’s desire and its limit. That’s why I cannot agree with the socialist’ or anarchist’s voice. In that I believe the Lacan has the reason why he did his work regarding human desire.